Dr. Amr Al-Azm

Dr. Al-Azm

Educated in the UK, Dr. Amr Al-Azm has held multiple archeological positions, teaching positions, and has excavated a number of sites. He was the Founder and Director of Scientific and Conservation Laboratories at the General Department of Antiquities and Museums (1999-2004) and Head of the Centre for Archaeological Research at the University of Damascus (2003-2006). He also taught at the University of Damascus through 2006. Currently, he is a professor of Middle East History and Anthropology at Shawnee State University in Ohio.

While working in Syria, Dr. Al-Azm was a first-hand observer and sometime participant of the reform processes instigated by Bashar Al-Assad thus gaining insights into how they were enacted and why more often than not they failed. Furthermore, he is a keen follower and commentator on current events in Syria and the Middle East in general and has written articles in numerous journals, and major media outlets including guest editorials for the New York Times, Time Magazine and Foreign Policy.

Image: Dr. Al-Azm with students in the Ma’ara Museum, 2005.

He is one of the founders and is a Board Member of The Day After (TDA) a Syrian-led civil society organization working on supporting democratic transition, justice, and sustainable peace in Syria. He was a member of the Executive Committee of The Day After Project and its Economic Restructuring and Social Policy working group. He coordinates the Heritage Protection Initiative (TDA-HPI) for cultural heritage protection at TDA. He also serves as a Co-Director of the The Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research (ATHAR) Project, an investigative study led by a collection of anthropologists and heritage experts digging into the digital underworld of transnational trafficking, terrorism financing, and organized crime. The ATHAR Project is affiliated with TDA-HPI and is a proud partner of the Alliance to Counter Crime Online.

Community Partner with The Arc/k Project

The Arc/k Project has worked with Dr. Al-Azm to help digitally preserve and protect cultural heritage sites in Syria, exchange training and translation services, and successfully test a methodology for teaching anthropology in group virtual reality with twenty academics and students. Through videoconferencing, Arc/k trained The Day After team in Syria how to use photogrammetry techniques to capture cultural sites, including UNESCO World Heritage Sites Dead Cities and Krak des Chevaliers. Dr. Al-Azm’s experiences in archaeology, research, international relations and education helps Arc/k expand our engagement with the multi-faceted, international efforts and applications for digital heritage preservation.

In September 2020, we interviewed him to learn more about his work and perspectives. In Part 1, we discussed the potential and impact of 3D and Virtual Reality in digital heritage preservation and education. Part 2 focuses on his work with The Day After, Heritage Protection Initiative and the ATHAR Project.

ARC/K: We’d love for you to share about The Day After.

AL-AZM: The Day After is a nongovernmental organization a few of my colleagues and I co-founded back in 2012. The initial idea of The Day After was born out of the need that became very clear to Syrians who were trying to not only come to grips with the whole Arab Spring, but who also were trying to address questions and concerns from both inside and outside Syria. There were people inside Syria asking me and others here in the U.S. including state departments and journalists –they were all asking us this question: “What is your vision?” “So ok, you all want change, you want Assad to go, but what is your vision? What is your alternative?” The Day After stemmed from that.

Information session on women’s rights in elections, The Day After

May 2011 was the beginning of the idea of forming the need for some sort of answer to that question of what is our vision. And the best way to answer that is to go to Syrians and say, ‘What do we think our vision is going to be?’

So The Day After started off as a project to bring together as many Syrians as we could. We set up a series of meetings in Berlin, from February 2012 through June 2012 with the view of looking at several core areas, including Transitional Justice, Constitutional Reform, Security Sector Reform, Economic and Social Reform. These areas were what we thought were core areas we could build a vision around. We brought all these Syrians together and we had a series of meetings to discuss them, and then we published The Day After document.

Theoretically, that should have been it. Given the Syrian opposition, in the midst of the Arab Spring and the ongoing uprising there– which was by then already shifting into a confrontation between the regime and the opposition– during that summer of 2012 – it gave them something. It gave them some sort of platform, something to look at.

Image: A collage for MENA protests. Clockwise from top left: 2011 Egyptian revolution, Tunisian revolution, 2011 Yemeni uprising, 2011 Syrian uprising. The original uploader was HonorTheKing at English Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Then the question was what do we do, and so then we created this NGO called The Day After, based off of The Day After Project. The Day After stands for The Day After Assad. That was the thinking because we all thought the regime was going to pull, sooner or later, and that this was going to be almost like a blueprint or some sort of vision of what could be done or what we could start working towards after. And so we took that and started to say, now why don’t we start to implement and follow up on our own recommendations, and on some of the things that came up and were discussed in the conversations that occurred in those meetings.

The primary mission of The Day After is to promote a democratic transition in Syria. We have five main sectors that I mentioned. We added cultural heritage as another main area that should become very important in terms of helping Syrians come together, helping Syrians transition from a war state to post-conflict stabilization and reconciliation.

ARC/K: In recent communications from The Day After, we see you’ve organized a Zoom panel ‘Justice for Victims in Syria – is it achievable through international tribunals?’ and you are raising awareness on the human right to civil documentation. What would you like to highlight in terms of TDA’s advocacy efforts and campaigns?

AL-AZM: A lot of the work that we do today in terms of advocacy – actual activity – is to help the world and help Syrians continue to understand what has happened to them throughout history, but also to seek to find ways to look for a post-conflict environment.

In order to have post-conflict, for example, stabilization and reconciliation…at one point, we will need to come together and talk to each other. There needs to be certain issues that are addressed.

How do we address the grievances? People have lost their life, their property. People have been imprisoned, tortured, killed. How do we manage this whole process of a transition and with a notion of justice? What does transitional justice mean to Syrians? Does it mean eye for an eye, in the extreme biblical sense of ‘you killed my brother, so I kill two of your brothers’? They are doing that right now. Or does it mean something else? What models are there from around the world of long-term extended conflicts, where they’ve had atrocities committed, and what can we learn from them?

Image: The Day After report, “So I’m Not Kept in the Shadows” Oral Memory: Syrian Women Survivors of Detention.

Survivors Program

One of the important things that TDA has been able to do is to go and get Syrians to talk about this; giving Syrians and women an opportunity to talk about some of the horrors they’ve experienced, in the survivors program. Empowering them, encouraging them and giving them the basic tools to tell their stories, we give them a safe space to express.

And remember, for women who have been violated, tortured, imprisoned, they have to deal with not just the terrors and horrors and trauma of it when they were taken and tortured, but they also have to deal with the aftermath effects of the society – the rejection, the stigmatization, and all of that that comes with it.

So you need to not just help these women find ways to tell their stories, but you also have to find ways to help their society figure out how to accept them, how to transition, how to adapt in this situation. So all of these are various ways in which TDA has tried to contribute.

ARC/K: We also read about your work to protect Syrians’ rights to civil documentation, and that the government is taking away these rights.

AL-AZM: Yes, if you don’t exist, they can take your land, your property. You don’t exist; you’ve been erased! One of the biggest concerns that Syrians have is property rights. Before the war, the government could reappropriate the land, misuse it to build buildings on it, and/or confiscate land with very small compensation. If you have no land records, they can just take it away. Another thing that was happening was that land registries were being destroyed willfully. You can’t prove it’s your land if it’s been destroyed. Victors can redistribute land among themselves.

Image: The Day After report The Property Issue and its Implications for Ownership Rights.

One of the programs that we started in 2014 was we went around to try to gather these documents from as many of these places, and scan these documents so that someone, somewhere in the future, would be able to say ‘I own this land. Even though you burned it and you destroyed it, here is some form of paperwork to show proof’. So they would be able to use these records and evidence as their home. We just signed an agreement with the Finnish government and another partner to help us manage a database. TDA has a lot of partners to gather this information from all over Syria.

ARC/K: Thank you for sharing about TDA’s advocacy efforts. We appreciate the multiple facets of your work and how TDA covers so much, with a holistic approach. Next, we’d like to talk about your efforts in combatting illicit trade of cultural artifacts. The Atlantic article “Archaeologists Defied ISIS. Then They Took on Facebook.” was super informative and heart wrenching. It really does paint a picture about how pervasive the illicit trade is and the difficulty involved with making even a small dent in it. Thanks again for including us.

The technology for identification will need to be at least as savvy and nimble as these networks. We hope Arc/k can serve our part. When you think of the intersection of technology and the efforts to stop international illicit trade, what are the technical issues? Who are the players that need to be on board?

Image: header image of The Atlantic Article “Archaeologists Defied ISIS. Then They Took on Facebook.”

AL-AZM: Illicit trade and antiquities–you have to see it as a bridge. You have a supply end and a demand end. Any military person or general would tell you, the only way to take a bridge is to take it from both ends at once. It’s much harder to take a bridge by taking one end, without taking the other. So when we come to illicit trafficking, sale, and trade, you have to take the supply end and the demand end. And there are different strategies for each end.

On the supply end, you’re going to use a range of different techniques, for example, increased cooperation from various local, state and non-state actors. State agencies, local law enforcement– you try and support them, educate them, and give them better tools. But you really need to work with local non-state actors because they face the greater burden, even in stable states, not just in war-torn conflict-ridden states.

Heritage Protection Initiative

The greatest burden there, especially in Syria, is going to be on non-state actors. That means working with local activists, archaeologists, communities and women. At our Heritage Protection Initiative website, you can see all the workshops that we’ve been doing, where we’ve been trying to educate local communities.

Remember, women and children are the real backbone for this. The women are critical because they’re looking after the children. The children, if they can be educated, will grow up one day and have this training with them. So it’s about raising awareness and just trying to explain it to people.

Cultural Heritage Tourism

A lot of it is changing attitudes as well. Let’s say you find a mosaic. If you rip that out, you just killed a goose to get one egg. If you leave that in, and then the state and local community come around, they help build that up into some local attraction. Then one day, tourists will want to come visit, and then you’ll have a sustainable business around it and for generations to come.

Subsistence Looting

So there are ways of addressing the supply side. Yes there are armed entities, armed groups, mafias, etc., but a lot of the looting is what we refer to as subsistence looting. It’s by people whose lives have been destroyed by the conflict. They know that there is stuff buried there, they know that there’s demand for it, and so they dig it up and they try to make ends meet with it. For a lot of people, that’s all they’re doing. They’re not doing it because it’s fun for them or it happens to be a passion. They’re doing it because they’re trying to make ends meet.

Strategies to Combat the Demand of Illicit Trade and Antiquities

Moving from the supply side to the demand side, that is something obviously very different. Here you’re talking about Western countries, rich clients who can afford to buy the stuff. And much of this stuff is about due diligence–changing the laws so that it criminalizes the trade in looted antiquities. Enforcement. You think about the FBI art crime squad. In 2015, there were only 15 or 18 people to cover the entire United States–300 million people. It’s pathetic! You have to put resources into this and you have to criminalize it.

And one of the ways to do that is to explain to people, hey, look if you are buying something that is looted, and especially from a war-torn region, there is a very good chance, that something in that piece, before it even gets to you, money would have been handed over at some point, to some very nasty local terrorist organizations, such as Al Qaeda or ISIS. So you can be prosecuted under the terrorism laws. It’s terrorism finance, because you are basically facilitating it. I think that will put the fear of God into them.

Right now, if I’m an art dealer, and you find a piece that is proven to have been stolen, and I’m selling it, I can just demonstrate good faith that I didn’t know. ‘So how come you didn’t know?’ ‘Oh the person who gave it to me swore on his mother’s grave that he didn’t.’ ‘Okay’. You think I’m exaggerating, I’m not.

Image: Plundered Heritage: The Antiquities Trade on Social Media, Fact Sheet 1, Alliance to Counter Crime Online

ARC/K: Ignorance is not an excuse.

AL-AZM: We’re talking about how lackadaisical it is, and we’re not talking about a backstreet deal. We are talking about major auction houses, major dealers in New York, London and Paris, who will take stuff on with the barest minimum of due diligence because they know, what’s the worst case scenario? They think ‘I’ll sell tens of thousands of pieces every year. If one or two of those get found out to be stolen, then I’ll just give them back.’ In return, tens of thousands of pieces are passing through the system just fine.

Even when we’re talking about the legal trade, it’s funny. You walk into the British Museum or the Louvre or anywhere else in those countries and most of the museums are filled with items from where, from outside. If you’re thinking of an American museum, it should be filled with only, I guess, local Native American material, if that. Where does the other stuff come from? It comes from the fact, that at some point or another, in the life of almost any item on display in the museum, or privately, in someone’s collection, it has been looted at some point or another.

We have a legal trade. We have a couple of interesting conventions, one of which is the Hague Convention of 1950 which came out of the second World War and the need to protect cultural heritage in times of war. There are certain rules about how you have to behave there. And then there was the 1970 UNESCO Convention – which basically says, that any object that has been around in circulation, but prior to 1970, you can trade it, as long as you demonstrate that. Anything after 1970, if it shows up on the market, unless it has an import/export license, then it’s looted. In 2019 there was a huge argument about an Egyptian piece being sold by Sotheby’s. It made all the big news and Egyptians went crazy. And the argument wasn’t about whether it was looted or not, the argument was whether it was after 1970. That was the fight. Noone was saying, you shouldn’t be looting it. They were focused on whether it was before or after 1970. The laws really have to change.

Even then, it might happen that you get a repatriation, and it’s not always straightforward. For example, let’s say they find a whole bunch of stuff from, let’s say Syria. Well no one is going to give Syria back its stuff. It’s in the midst of a war, you have a regime that is a pariah. If Afghanistan were still under the Taliban, would you give them back a whole bunch of stuff that would be confiscated? No, it’s very complicated.

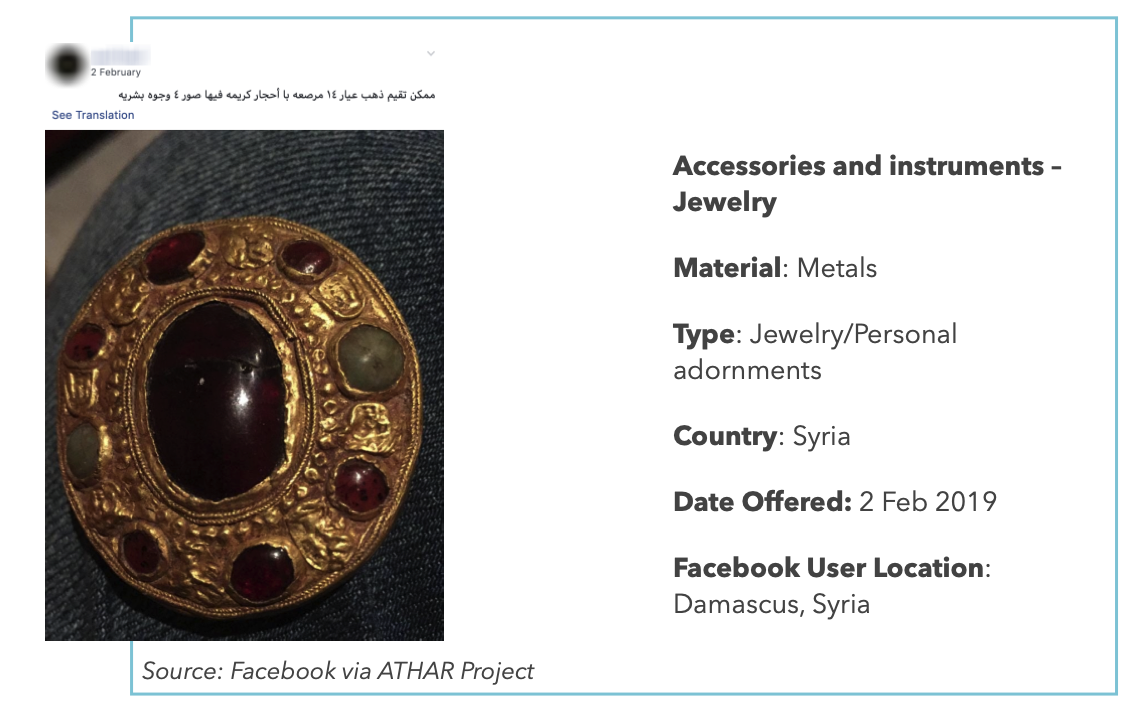

Image: Example of a Red List artifact from Syria being trafficked on Facebook in ATHAR Project’s report ‘Facebook’s Black Market in Antiquities: ICOM Red List Artifacts Offered on Facebook’.

So the basic thing is that it’s not encouraged in the first place and we need to create the systems and the means to really make it very hard for people to openly trade what is essentially looted antiquities. Then, with Facebook and social media platforms, it’s open season. You have to stop it from being traded and sold openly. There are no checks and balances on that.

ARC/K: You bring up a good point. In a sense, as Americans, we sometimes think that technology is going to save us from everything. But, here we go, with Facebook you can do anything, send anything to anyone at any point, create these social networks, and yet it’s created a blossoming of these illicit trade networks.

And on the other side of that, there is the institutionalization of the looting by the larger auction houses. Like you said, it’s like the cost of doing business. They might be saying, oh well, there might be a few. Could you see a social media campaign used against them, to shame them, to get them to change their ways beyond a legal framework?

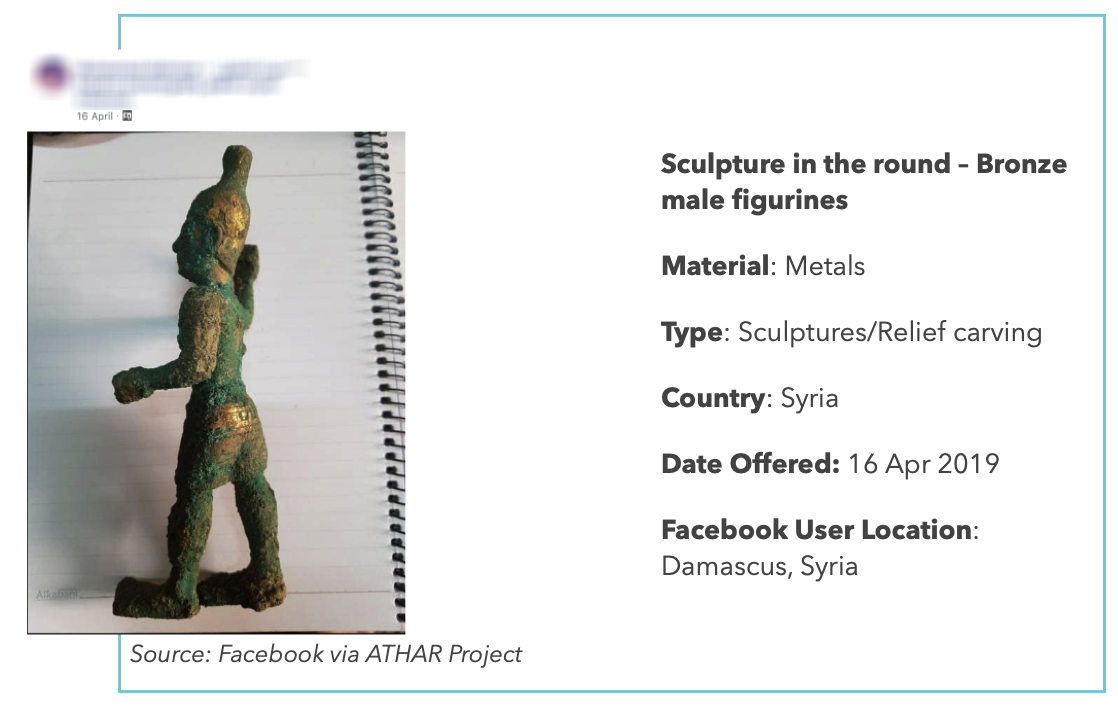

AL-AZM: I think there’s already a lot of that happening anyway. The only real change would be a change in the law–when you criminalize it. So that when you get caught doing something like that, it’s not going to be a slap on the wrist and you give it back. Instead, you’re going to go to jail for a very long time, because you’ve just been aiding and abetting terrorism and terrorists. That’s when you’re going to get a wake up call.

Image: Example of a Red List artifact from Syria being trafficked on Facebook in ATHAR Project’s report ‘Facebook’s Black Market in Antiquities: ICOM Red List Artifacts Offered on Facebook’.

ARC/K : We’ve also brainstormed a bit about a concept where we could help train Syrian expats to comb through Facebook data and monitor stolen Syrian cultural heritage assets. We could work with database partners and Interpol to track these digital objects.

AMR: Right now, we’re looking at between 8 and 10,000 photos. They could grow so much more. We’re seeking funding in order to hire a few people to work on this archive and set up a database. We could have the team on the ground continuing to take updated photos and images, where you look at the archives of what we already have and you file those in terms of the damage, what was there and what came up. You could also then design and develop off of that structure, for emergency intervention projects to help save buildings which may be unstable or on the verge of collapse.

Image: Plundered Heritage: The Antiquities Trade on Social Media, Fact Sheet 2, Alliance to Counter Crime Online

ARC/K: We look forward to keeping in touch about this approach of combating illicit trade. We are grateful to continue working together towards solutions and to further developing our research of 3D and VR applications in heritage preservation and protection. By empowering cultures in crisis to protect their own identity against illicit trafficking, digital poaching, vandalism, and ideological/religious warfare, we hope to put digital tools in the hands of those that can make a real difference.